By: Macy Bischoff

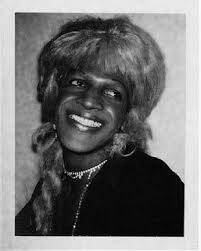

As a homeless, prostituting, trans woman of color, Marsha P. Johnson could have been “perceived as the most marginalized of people”, facing frequent acts of violence and discrimination during her short life (Susan Stryker qtd. in Sewell 2018). Rather than allowing the circumstances to weaken her spirit, she utilized her vulnerable position to bring hope, love, and justice to her community. Her existence challenged cultural norms, and out of the discomfort that her actions cultivated, society and history have attempted to silence her story even after her death. However, with the recent emergence of trans studies in academia, people outside of the LGBTQ+ community are finally discovering the incredible legacies of liberation pioneers such as Miss Johnson (Nothing). Despite society’s attempts to conceal her mark on the world, Marsha P. Johnson revolutionized the trans rights movement through her demonstration of powerful activism and radical love.

As an advocate in the gay liberation movement, Marsha was first known for her actions in the 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn. Said to have initiated the people’s resistance against the police, she threw “the shot glass heard ‘round the world” to take a stand against the unjust raid (Pay It No Mind 2012, Sewell 2018). Following this event, she participated in numerous AIDS protests and marched in gay pride parades as she continued to fight for gay rights, claiming, “As long as gay people don’t have their rights all across America, there’s no reason for celebration” (Pay It No Mind 2012, Marsha P. Johnson qtd. in Sewell 2018). However, this movement for gay liberation continually placed the fight for the rights of transgender people “at the periphery” of the cause, ignoring the needs of the most oppressed by society (Shepard 2013). Recognizing this fatal flaw, Marsha P. Johnson joined with Sylvia Rivera to create an organization named “STAR”, or “Street Trans* Action Revolutionaries” to serve the homeless trans youths that were forgotten by the gay rights movement. STAR provided food, clothes, and shelter to those in need, and highlighted the necessity of organizations specific to the cause of trans folk within LGBTQ+ activism (Nothing). This idea of creating a separate entity for the trans rights movement is echoed in the literature of trans studies, molding queer theory in this day and age (Shepard 2013, Stryker 2010).

Through the work of STAR, Marsha not only gave the marginalized the means of survival, but she also brought dignity to their lives, caring for each person she encountered. Her warm, generous personality is remembered by the people whose lives she touched, many calling her a ‘saint’. Despite personally living on the streets, Marsha sacrificed her resources to ensure a brother or sister could live another day. Out of this love, she gained a specific following, and began to shift her community’s perspective of her identity. After Marsha’s body was recovered from the Hudson River in 1992, and her death was ruled to be a suicide without proper investigation, her friends and admirers petitioned to hold her funeral in the street so that all may mourn the tragedy. Surprisingly, the chief of police agreed, saying, “Marsha was a good queen” (Pay It No Mind 2012). Marsha’s embodiment of saintly love attracted many to her life, changing the way she was perceived as a trans woman, and expanding her audience for her works in the trans rights movement.

Marsha P. Johnson lived a counterculture lifestyle, expressing her womanhood through the dichotomy of strength in activism and gentleness in love. Her actions in the fight for gay and trans rights were not accepted by many, and she endured terrible hardships for living so boldly and authentically. Refusing to accept the cisgender, heteronormative ideals of her society, Marsha began to generate a positive view of her trans identity within her community by demonstrating kindness and generosity to trans people in need (Pay It No Mind 2012). Her activism in the Stonewall riots, AIDS protests, and STAR formation also fought to provide all people with basic human rights, while identifying the importance of a separate trans voice in the movement for equality, a foundational idea in the new subject of trans studies that attempts to educate our world and strengthen the cause for transgender rights (Sewell 2018, Shepard 2013, Stryker 2010).

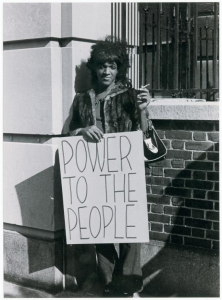

“We believe in picking up the gun, starting a revolution if necessary” (Marsha P. Johnson qtd. in “Rapping with a Street Transvestite Revolutionary: An Interview with Marsha P. Johnson.”, Davies 1970).

*Though commonly used in Marsha’s time, the term “transvestite” is not widely accepted by the transgender community. Out of respect, I have chosen to simply say ‘trans’, or ‘transgender’.

Works Cited

Davies, Diana. Marsha P. Johnson: Power to the People. New York City, 5 Oct. 1970.

Nothing, Ehn. “Queens Against Society.” Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonist Struggle, pp. 3–11.

Pay It No Mind: Marsha P. Johnson. Dir. Michael Kasino. Prod. Michael Kasino. Redux Pictures, 2012. Academic Video Online: Premium Database. Web.

“Rapping with a Street Transvestite Revolutionary: An Interview with Marsha P. Johnson.” Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonist Struggle, p. 22.

Sewell, Chan. “Marsha P. Johnson.” New York Times, Mar 11, 2018. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/2012602741?accountid=15131.

Shepard, Benjamin. “From Community Organization to Direct Services: The Street Trans Action Revolutionaries to Sylvia Rivera Law Project.” Journal of Social Service Research, vol.39, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114., doi:10.1080/01488376.2012.727669.

Stryker, Susan. “(De)Subjugated Knowledges : An Introduction to Transgender Studies.” The Reader-Reader, 31 July 2010, readersquared.wordpress.com/2010/07/31/tsr-desubjugated-knowledges/.

Warhol, Andy. Marsha P. Johnson. Pittsburgh, 1975.